Summer sales of residential real estate aren’t what they used to be on any end of the Florida market, high or low, east or west.

From the $200,000 range to the $10 million range or more, people have gotten savvier about current markets and for-sale properties, an important reality in a summer season that seems more complicated this year than many others.

Here’s why: There are uncertain interest rates. It’s an election year with no incumbent president on the ticket, and it’s post-pandemic, with new, post-pandemic expectations for living and working.

Markets may be more vulnerable to climate change or the perception of it, which plays a role in how, where and even if people think about buying waterfront property.

And finally — to round out a challenging quintet of summer factors — new state laws have gone on the books requiring more demanding construction safety standards in condominiums. That’s helping drive up homeowners association and maintenance costs in older ones, which puts a burden on the owners of older condominiums and has contributed to the significant cooling off of the condo sales market this summer, Realtors say.

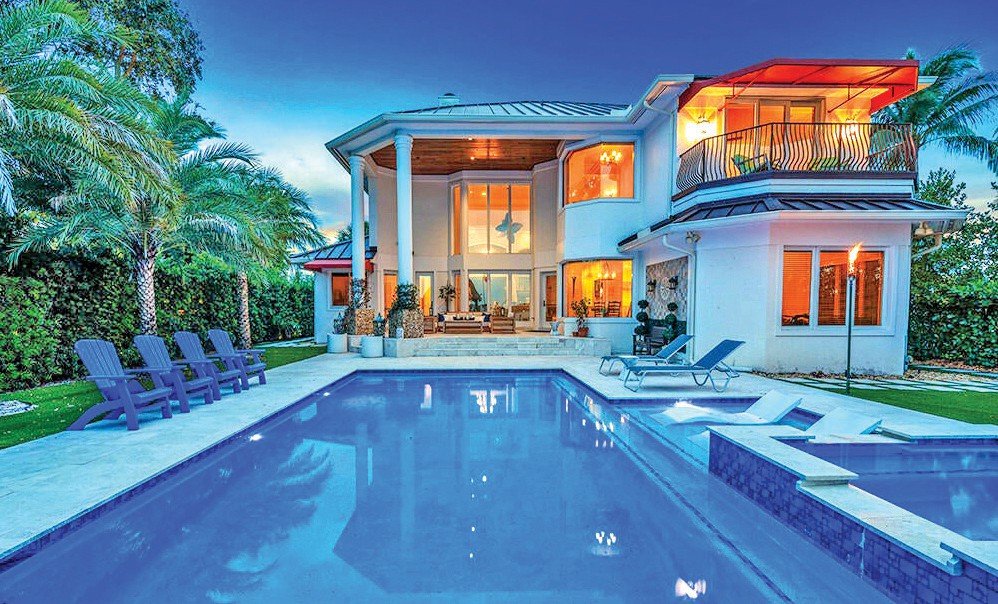

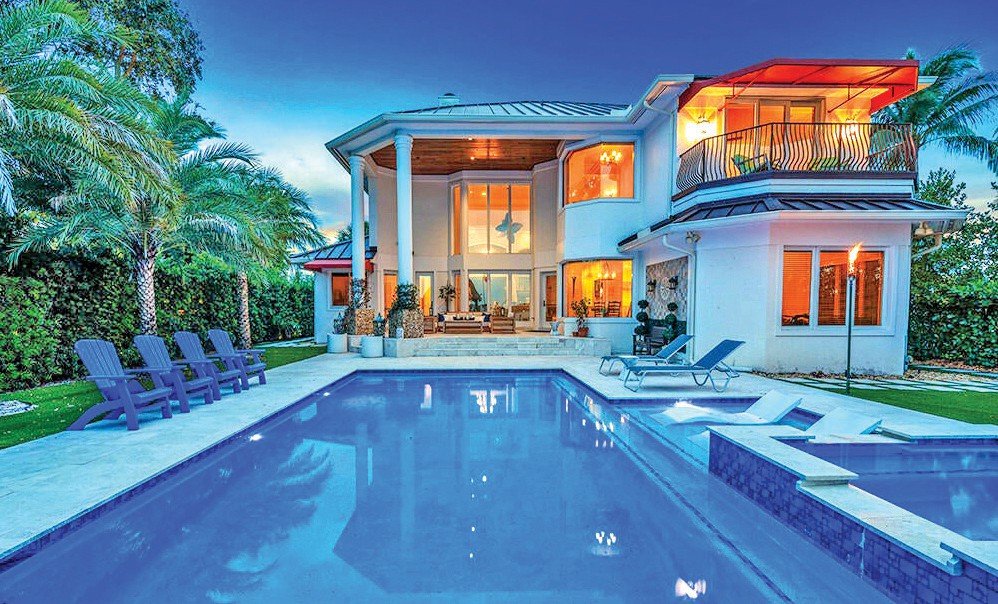

This home at 18241 Perigon Way in Jupiter, Fla., listed by Michelle Noga and Paula Wittman at William Raveis, is available for $7.9 million. The two Realtors say home prices are keeping steady and that properties used to sell in days instead of in the weeks or months that it takes now in some cases. This property has been listed since May.

But this summer, despite all those factors, the markets are beginning to settle, almost like the pre-Covid days, according to several Realtors who have been in the business since well before that.

“I think we’re finding younger buyers buying condos, like pre-retirement people who can work remotely,” says Pam Lemmerman, a Realtor for Barclays Real Estate Group who sells homes and condominiums on both the north and south sides of the Caloosahatchee River, a mile wide in downtown Fort Myers and traditionally an enviable living location all the way to its mouth in Charlotte Harbor and the Gulf of Mexico near Sanibel Island.

Hurricane Irma in 2017, a devastating blue-green algae and red tide assault that lasted almost 14 months on both the east and west coasts through 2018, and then the catastrophic Hurricane Ian in 2022, two years after the pandemic that resulted in a buying spree by northerners trying to move into Florida and driving prices up, all hit the market hard.

In Lemmerman’s view, “the news gives us a bad rap.” The housing market may have taken some of the blame for sharp rises in homeowner’s insurance, car insurance and flood insurance.

“They redid all the flood zones,” Lemmerman notes, “because they had to. But now, if you buy something in a flood zone, you have to pay (very high) flood insurance.”

But the market shows signs of coming back.

“We’re seeing finally some more buyers looking at condos,” Lemmerman says.

“I don’t know if they’ve been waiting for the dust to settle, or waiting for assessments to be paid, or something else — and yes, HOA fees are going up. By 2025 (according to new laws that followed the Surfside collapse), they have to have their reserves in place. So these buyers may want to lock in something before prices go higher.”

In Naples, Izabela Wright, a broker and owner of Wright Real Estate who speaks both Polish and Spanish, also suggests a steadying effect on the market this summer.

“Buyers have more home options as the inventory of properties continues to rise compared to the last three years,” she says.

“In June, the 59% increase in inventory resulted in an available pool of 4,680 properties compared to only 2,943 properties during June 2023.”

While summer sales in Naples are typically slower than winter sales, as they are in most markets, she adds, “the days on market in June increased 56%, to 78 days, up from 50 days in June 2023.”

Before the pandemic, though, in 2019, “We were between 90 and 120 days on the market. So we are still well below our traditional average.”

For Phillip and Spencer Rigsby, a team at Premier Sotheby’s International Realty in Naples, the summer has been a good one, so far, and shows no sign of becoming something else.

“We’re back to what I consider my normal summer times, the pre-COVID years, kind of a 2019 and earlier pace,” Phillip Rigsby says.

He carried on a career first in the golf world where he played and owned a Bonita Springs shop, then for more than eight years as a Realtor in the Naples area.

The pace and pattern of his customers have favored his decent summer, he says.

“A lot of my customers come down in season, rent for a month or two, go home, then come back for a week in summer and do their shopping. The restaurants are slower and people can get into restaurants, tee times are easier, traffic is lighter, it’s a nice time to shop. And there’s less buyer competition in town.

“I had some folks in town just last weekend. They were down in February, they went home, they came back and narrowed it down to the country club they’re looking for. Coming back in summer, as long as you find what works for you on the market, is a great time to buy.”

Were they simpler times?

What may appear to have been simpler times before all this unfolded probably were — but not always helpfully. Brokers and agents once talked business on landline telephones, and potential buyers out of state once had to travel to get a good look at properties and locations attracting them, which not everybody could do, recalled Denny Grimes, president of Denny Grimes & Team working in Lee and Collier. He started selling homes on the southwest coast 40 years ago. e

Th problem with the good old days was often knowledge, he suggested: Information from a distance was sketchier.

“My snowbird friends had no earthly idea what was going on down here in the real estate market in real time” — at least not when they weren’t here, said Grimes.

Now, notes Candace Jorritsma, vice president of sales and marketing for El-Ad National Properties, “When the pandemic happened, we were in phase one, with 121 units, and it shifted everybody’s gaze.”

The company’s new luxury product, ALINA in Boca Raton, is set to complete its second phase in two parts this year, including a smaller building with 30 residences and a larger 152-home building offering prices in the several millions.

Few or no landlines were involved in sales.

“People were afraid to travel but they wanted to move,” Jorritsma said. “So our marketing focused on virtual tools and tours. We sold to some people who never set foot on the property. The pandemic changed everything. But we got through phase one successfully, people saw what we delivered, and that contributed to our success in phase two.”

That’s already 80% sold, she said. “So this last year the market got back to its regular seasonality.”

Sort of.

Long before all that, however, many property owners once locked up and headed north in April or May to open their pools and their permanent homes in the places they grew up, returning to Florida in November or December, Grimes recounted. Populations ebbed and flowed like the tides, a fact that became immediately apparent on regional roads where drivers infrequently encountered traffic jams or long back-ups during the long, hot, wet summers.

This home at 18241 Perigon Way in Jupiter, Fla., listed by Michelle Noga and Paula Wittman at William Raveis, has been on the market since May. COURTESY PHOTO

That was true on both coasts. The population of permanent residents in Lee and Collier counties 40 years ago amounted to just over 300,000, not 1.3 million, roughly the current count. And in Palm Beach County, almost a million more people are permanent residents in 2024 than in 1984 — the county’s population is about 1.55 million today, the Census Bureau estimates.

And for all those old-timers, “the only information they got came through the newspaper on Saturdays and Sundays,” Grimes said. Realtors tended to pack their advertisements into weekend editions of the daily rag, “so people learned about our markets through the proverbial carrier pigeon.”

And now, any person with a computer and Internet access can learn how complicated the market can be, what those in the profession are saying about it or about properties, and exactly what properties and their neighborhoods look like, not to mention what the communities, the schools, and the access to culture looks like — all nearly instantly, and all from homes or offices in New York, New Jersey or Connecticut, in the Midwest or California, or anywhere else, for that matter.

That means the summer market may prove more vigorous than once upon a time. But other factors besides the Internet weigh in significantly.

NOGA

Complex factors

“Summers during an election year are notoriously slow,” said Michelle Noga, a luxury properties specialist with her partner, Paula Wittman, at William Raveis in Palm Beach County. “It doesn’t matter who’s up, or what side of the aisle they’re on, that happens.”

Elections, along with such indisputable realities as climate change and the effects it might have on some real estate on a water bound peninsula — not to mention vagaries like a pandemic and its market aftermath or new state laws affecting condominium living — all play a role in a given summer market like this one.

“When there was cheap money, and no going into the office, we saw this migration here, with cheap money driving up the prices of homes,” Noga explained.

Even in summer—say, the summer of 2021 — “homes might be on the market for three days, instead of three months,” Wittman said. “And now, prices haven’t gone down, and they’re battling insurance.”

Insurance doesn’t seem constrained by physical laws these days, either, Realtors suggest. It only seems to have one direction: up.

But that hasn’t altered the desire or imperatives for some.

Realtors Michelle Noga and Paula Wittman say home prices are keeping steady and that properties used to sell in days instead of in the weeks or months that it takes now in some cases, like this property in Jupiter, Fla., for $7.9 million. COURTESY PHOTO

“We have two types of buyers,” Noga said. “The luxury buyer looking for a second home” — and maybe they’ve decided Florida should be a permanent residence, not just a vacation retreat, she suggested — “or people from other markets, such as those with school-age children.”

Schools, then, become a significant factor, regardless of climate, pandemics or elections — or questions about how far interest rates might come down.

“We have a client like that we’re trying to find property for now,” Noga said. Somebody who typifies a summer market buyer because they wanted to be in a new home before the beginning of the school year.

And not just any home or school.

“They want to be in the Jupiter school district because it’s so highly rated, and they want a half-acre,” she said. Jupiter public schools are part of the Palm Beach County public school system.

Her buyers aren’t the only ones; schools can be a Florida-wide issue, especially as the state’s population of businesses based here increases, and younger families with children follow them, since they employ the parents.

“I used to read about the boom-bust of Florida, the low-interest rates when people bought property, followed by market corrections or even collapses when everything was dumped, but I’ve been here and watched for 10 years now,” said Adam Gottbetter, a vice president of Finance & Development for the developer of Glass House Boca Raton.

Glass House is a 10-story condominium building and his development company is called 280 E Palmetto Park Road, LLC.

“I’ve watched a real shift of lifestyle, with remote work, the chance to live in a no-income tax state with great weather and still be involved in a business that might be based in New York — and all that’s a real change.”

For most people looking to move into Florida — or for Floridians aiming to upgrade — “there are big four issues,” he said, whether in summer or winter: “Where the kids go to school; where do I have to go to get (very fine) doctors; what clubs can I join; and where can I live that gives me all that?”

Glass House, with price ranges currently from $2.5 to $6.1 million, represents a new development paradigm some less pricey developments may begin to practice as well: putting much of that in place for potential buyers, including very good private schools and health care.

“So we made a deal with Sollis Health — they operate in New York, Miami, both Boca Raton and Palm Beach — and they have concierge practices, they bring in the best. You don’t have to go find them. And that’s attracting people from out of state.”

An advertisement for Sollis Health says, “Elevate your emergency-care experience with Sollis Health, the premier members only provider for your everyday and urgent care concerns.”

In addition, he said, “Boca Raton has the highest concentration of private schools…. and Florida has to address that with more school resources and an expansion of schools and school choice. ”

With all of that, there’s another factor, too, he says: Affordable housing. When it exists, life is better for people who live in a Glass House and depend on workers. All of them benefit from living in close proximity.

Boca Raton, he says, is a community whose planners anticipated some of this.

“So we opened our sales gallery May 1,” Gottbetter said. “We had people interested in property from lots of areas, but there were also a good percentage of locals.”

Privacy and exceptional security are two drawing cards, along with this seemingly counterintuitive objective: “We now have people come to us who do not want to live on the ocean. Whether it’s climate change or whatever the reason is, they don’t. One issue is storms” — that’s primarily a summer issue —and another may be just the wear and tear and the maintenance issues associated with saltwater.”

GUTMAN

Phil Gutman, founder of Miami based Gutman Development Marketing, takes his business straight to the mountains in summer — not the Southern mountains but the higher ones: the Rocky Mountains.

A fine polo player born and raised in New York where he never saw a horse in his youth, he came to Florida two decades ago but maintains a second home in Aspen, Colo. There, he spends summers selling Florida real estate.

He remembers the old days.

“Miami used to have an immediate slowdown once the summer months arrived, and New York and New Jersey were the prime feeder markets,” he said.

But now that’s changed — Miami is an international city and South Americans represent a feeder market as well, often visiting in the summer, not the winter — so south Florida may draw people that California, for example, with an ocean and warmth in the southern part of that state, may once have attracted.

“There’s a mass exodus from California as a state. Whether it’s regarding taxes or the government” — and perhaps the summer blight of wildfires there is a factor — “it’s not as desirable as it used to be. But Miami is an international city, not just a vacation spot.”

Among the biggest challenges in the market there now is climate change, he says, “something we can’t get away from. We’ve been talking about it for two decades since I moved to Miami. But now there’s more focus and attention on it. So when somebody is spending $10 million to $20 million on a single-family home, they’re looking for homes with higher elevations.”

New construction in high rises starts high, it doesn’t just end high nowadays.

And new state laws that in some cases require such a reality are creating a change, too, in the old waterfront Florida. Aging condos are likely to disappear by mid-century or so, Gutman suggested.

“When we design buildings now, we’re including business centers, workstations, grab-and-go markets — whatever we can to make it more (self-sufficient) as a living space,” he explained.

“There’s a shortage of land, we can’t make any more oceanfront properties, and it’s tight in downtown areas as well, so by mid-century…” By mid-century, he says, the old condominium buildings all may have to come down.

“There’s a lot of scrutiny and critique of the older buildings, and their maintenance costs and HOA fees. The owners sometimes can’t afford the maintenance and assessments,” costs prompted in part by the new laws, and by need.

“We’re acquiring several different condos — we’re in the process of buying out those old buildings” — and that means owner by owner.

Denny Grimes points to the condo slowdown in data for Lee and Collier counties — the Fort Myers and Naples markets — that reveals how big the impact may be.

Between 2020 when the pandemic arrived and 2021, condo sales jumped from 10,931 to 15,027, his figures show. But in 2022 they dropped by more than a third, to 9,705, and last year, 2023, the sales came in only 8,133. The majority of those came in quarters one and two of the fiscal year.

And this year? As of July 1, only 4,320 condominiums had sold in the two counties. ¦