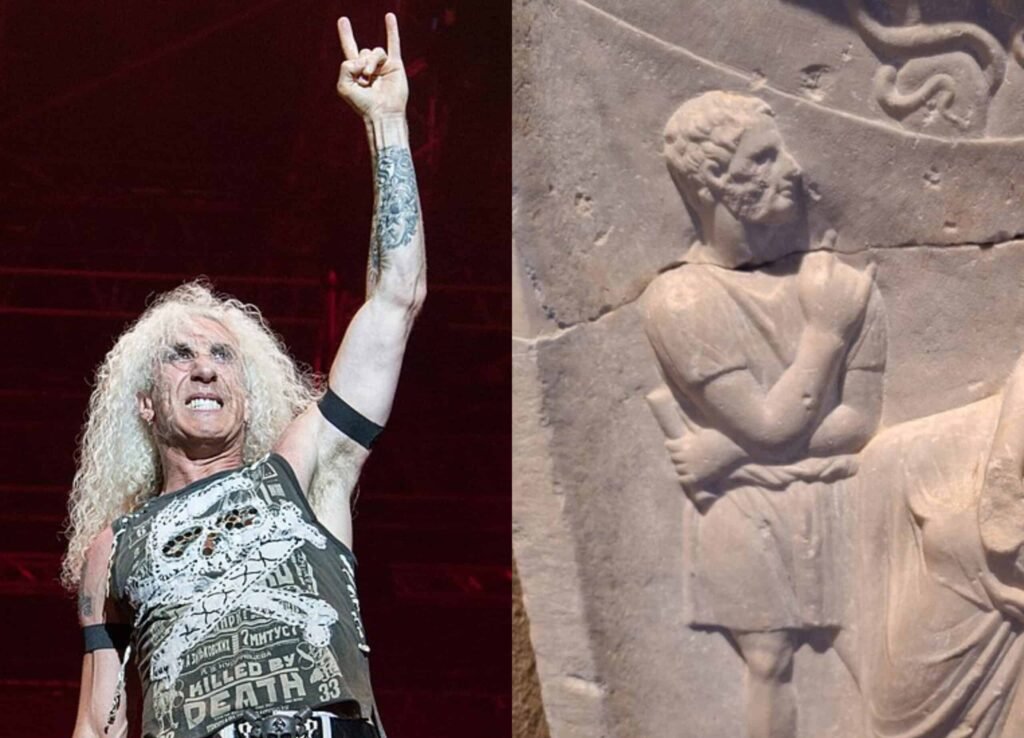

A funerary stele in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece, has reignited debate over the origins of the “devil’s horns” gesture. The relief, dated to around 50 BC, depicts Gaius Popillius seated on an ornate throne while an attendant holds a scroll and forms the famous two-finger salute.

According to the museum label, the sign can be interpreted either as an apotropaic symbol or as a conventional “gesture of speech” in dialogue scenes. This ambiguity hints at a long prehistory for the sign now so familiar at rock concerts.

The funerary context matters, as grave art often compresses daily life, the religious beliefs of the deceased, and public performance into a single scene. What might seem like a simple hand gesture can convey multiple layers of meaning—reflecting not only the individual but also the broader society.

The story behind the devil’s horns hand gesture

Beyond this lone stele, historians point to a widespread Mediterranean tradition. In Italian folk culture the mano cornuta, the horned hand made by extending the index and pinky fingers, has been used for centuries to ward off the evil eye (malocchio). Museum collections describe such amulets as protective charms rather than occult emblems, often crafted in coral or silver and worn to deflect misfortune.

A related charm, the mano fico—with the thumb thrust between the index and middle finger—appears alongside this in numerous collections as another “everyday” safeguard rather than a sinister emblem. Such vernacular objects suggest a long, practical history for horn-like signs in the folk tradition of many Mediterranean nations.

Meanings also shift based on context. In Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, pointing the horns upward at someone can be insulting and imply cuckoldry. That double meaning, protective in certain settings and offensive in others, helps explain how the gesture could appear on funerary art without any link to modern subcultures.

A sculptor drawing on familiar visual language might intend either to shield the deceased from misfortune or to simply mark speech in a carved exchange between the living and the dead. The same configuration can be understood as a ward, warning, or jab depending on who makes it, to whom, and where.

The role of hand gestures in antiquity

Classical sources make clear that gestural language was integral to public life. Ancient orators and theater performers deployed a codified repertoire of gestures to signal emotion, emphasis, and turn-taking. Rhetoricians such as Quintilian did not catalog the “horns” explicitly, but they did discuss how particular finger positions shaped meaning—from supplication to denunciation—and how audiences learned to read those cues.

Funerary reliefs, which often imagine the deceased in dialogue with the living, borrow this convention too. A raised pair of fingers beside a scroll could therefore indicate speech, authority, or protection without necessarily pointing to a single fixed interpretation. Parallels exist outside of Europe as well. In Buddhist iconography, a similar configuration, the karana mudra, is explicitly apotropaic and is used to repel negativity and evil forces

Reference works and temple sculptures alike confirm the mudra’s appearance in depictions of the Buddha and bodhisattvas, demonstrating that horn-like hand signs have long been linked to repelling, rather than inviting, malignant or evil forces. The recurrence across cultures suggests something intuitive about a pointed, two-pronged hand shape as a symbol of expulsion and boundary-setting.

The modern use of the devil’s horn gesture

The jump from ancient times to a hard rock or heavy metal arena salute is a late-20th-century story. Heavy metal singer Ronnie James Dio is widely credited with popularizing the horns on stage after joining Black Sabbath in 1979. Dio said he adopted it from his Italian grandmother’s habit of using the gesture to ward off the malocchio (evil eye), creating an accessible, nonverbal connection with audiences that differed from the peace sign used by his predecessor, Ozzy Osbourne.

Music histories and interviews trace how the sign rapidly spread through metal culture as bands, road crews, and fans mirrored one another at shows and in photographs, transforming it into a badge of membership. Not everyone agrees on firsts in pop culture, however. Photographs and testimonies show earlier, scattered evidence of the use of the devil’s horn gesture, from psychedelic rock to occult-themed acts in the late 1960s.

The truth is none had the same transformative impact as Dio, who popularized the sign before arena-sized audiences. Regardless, the modern association with heavy metal is less an invention than a repurposing, in which a familiar apotropaic or insulting sign sheds its ambiguity and becomes a symbol of amplified sound and shared identity.

The gesture’s visibility even spilled into law. In June 2017, KISS bassist Gene Simmons filed (but then swiftly withdrew) an application to trademark a thumb-out variant of the hand gesture, a move widely questioned given its long folk history and overlapping uses. Commentators also noted that the thumb-out version coincides with the American Sign Language sign for “I love you,” making exclusive rights difficult to sustain.