Precious metals are shining this year, with being now one of the best-performing asset YTD, with closing in on its heels.

Introduction

Gold occupies a special place in human history as the quintessential haven asset; with evidence of humans attributing value to gold dating back to the Varna Necropolis 6500 years ago. Precious metals serve many purposes from jewellery to high tech, yet perhaps most important is their ability to preserve investors’ wealth in times of uncertainty.

Central to gold and silver’s value in times of tumult is their tangibility. Compared to other more “synthetic” assets, investors are given confidence by the fact they could have the equivalent of their investment sitting on the table in front of them. Beyond the metals’ strong market performances lies a deeper question: is the renewed demand for tangible assets the first sign of a broader shift back towards a metal-based monetary standard?

Why a Gold Standard and Not a Silver Standard?

For centuries, silver has been the predominant metal associated with money. Before the 19th century, the global economy operated on a tri-metallic base of gold, silver, and , but the dominant force was effectively a de facto silver standard. The increasing supply of silver, combined with its declining value relative to gold and copper, ensured its widespread and central use in everyday trade and currency systems.

The 19th century brought what became the “Great Debate” over whether gold or silver should become the official standard. Early attempts to stabilise both metals through national currencies defined by fixed exchange ratios, most commonly around 15.5 to 1, soon grew unstable as supply and demand shifted. As market values diverged from state-imposed rates, distortions emerged, laying the groundwork for the decline of bimetallism.

As global trade expanded under Great Britain’s dominance, nations found political and economic advantage in aligning with a gold-backed system. Practical considerations reinforced this choice: the gold standard allowed silver to serve as token money, with face value exceeding its metallic worth. Because silver had been demonetised, it provided stability to the system and avoided the pitfalls of Gresham’s Law, which would have driven gold from circulation.

Ultimately, the abandonment of silver was not because gold was “better money” in an economic sense. Silver continued to function effectively in domestic and regional trade. But at the international level, the political weight of Great Britain and its trading partners, combined with the instability of fixed bimetallic ratios, pushed the world toward a gold standard. The choice reflected power and pragmatism more than the intrinsic properties of the metal.

Source: Bloomberg Professional (GOLDS and XAG)

This international shift culminated in the formal adoption of the gold standard, a system in which a country’s currency is directly tied to gold. The fixed price of gold served to determine the value of the national currencies. The gold standard thus tied currencies to a tangible resource, in contrast to fiat money, which rests on government authority alone.

The Current Gold Standard Debate: 2025 Economic Pressures

Even though no country uses the gold standard today, heightened geopolitical and economic uncertainty of the past years revived calls for its return.

Gold has returned to the centre of the financial stage propelled by a flight to safety that is reshaping the global economy. In recent months, investors have favoured bullion over other asset classes as rising geopolitical tensions have boosted its appeal as a safe haven.

One of the key drivers of this rally is the risk and uncertainty engendered by US foreign policy. President Trump’s trade war, combined with growing geopolitical tensions and questions about the long-term role of the , have all contributed to an impressive surge in gold prices.

Markets were rattled by the president’s “liberation day” tariffs, pushing investors towards assets that could shield them from the fallout. Trump’s later assurance that gold would not be subject to tariffs highlighted its enduring role as a safe-haven asset in market uncertainty.

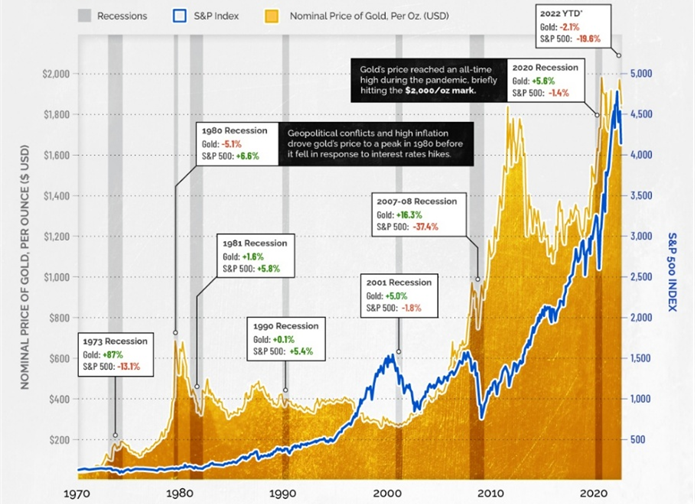

Source: The evolution of gold’s price during recessions, Elements by Visual Capitalist

History offers the same lesson: in times of geopolitical and economic instability, people tend to prefer currencies that hold sustainable value over those with diminishing value. This dynamic was highlighted when gold surpassed the euro last year to become the world’s second-largest reserve asset among global central banks.

This year, gold’s rally past $3,000 per ounce revived memories of earlier crises. Bullion broke $1,000 during the 2008 global financial crisis and $2,000 during the Covid-19 pandemic. These milestones underline the powerful influence of geopolitics on gold’s valuation. When the global economy’s foundations are in doubt, gold emerges as an anchor.

It is the ultimate “confusion trade”, offering an apolitical store of value that is not subject to political influence. The ripple effects have not been limited to gold: silver too benefited from these times of crises, attaining its highest level in 13 years.

With growing doubts about the health of the dollar, still the de facto reserve currency, the world’s traditional haven asset is enjoying renewed attention. Economic and political instability in the US has started questioning the dollar’s long-lasting hegemony, making other countries nervous about holding reserves in US assets.

Investors are turning to gold, and increasingly to silver, as hedges against a weakening US dollar. This sudden distrust in major currencies is another factor fuelling those metals’ rally, as in periods of crisis it is reassuring to hold an asset with enduring value.

Safe-haven buying has only added momentum to a rally already supported by central bank purchases. For decades, reserve assets were concentrated in US dollar assets, especially the $29tn US Treasuries market. However, in recent years, central banks have returned to gold in an effort to reduce their reliance on the dollar. China, India, Russia and several other nations are leading the shift, highlighting growing doubts about the long-term stability of the dollar.

While market dynamics have fuelled gold’s rally, political momentum is increasingly shaping the debate around gold. In the United States, calls for a return to the gold standard are no longer confined to academic debates. Florida has already taken a concrete step by announcing that gold and silver coins will become legal tender in 2026. This reflects growing interest in reintroducing metals into everyday money use, as gold and silver coins with a certain purity level will be accepted as money.

At the national level, the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, a proposed blueprint for Trump’s second term, evokes the elimination of the Federal Reserves in favour of a return to the gold standard. These moves illustrate how current geopolitical and economic instability, combined with distrust towards fiat money and central banking institutions, are bringing the gold standard back into political discourse.

The Case for Return to Gold/Silver Standards

Advocates of a return to a gold or silver standard argue that anchoring money to precious metals would bring order and stability back to the financial system. With climbing US debt and scepticism about fiat currencies deepening, they believe that tying money to precious metals would provide a safeguard against government overreach and monetary instability.

A central argument is that the gold standard promotes price stability. Under a metallic standard, currency issuance is limited by gold or silver reserves, preventing governments from inflating currencies at will. Inflation becomes less common, and the threat of hyperinflation is prevented altogether since money can only grow as fast as new reserves are discovered. Historical periods under a metallic standard are often cited as examples of relatively stable purchasing power.

Supporters also argue that such a system would benefit international trade. A gold-backed system creates fixed exchange rates among participating nations, reducing currency volatility and offering greater predictability. This stability fosters confidence among merchants and investors alike, encouraging cross-border commerce and long-term investment.

The case of Ghana in November 2022 offers a recent illustration: facing pressure in traditional currency markets, the country signed a provisional agreement with the United Arab Emirates to purchase oil in gold rather than US dollars. Beyond securing energy supplies, the deal also aimed to reassure Ghana’s economic partners of its solvency at a time when traditional currency markets questioned its financial standing. This example illustrates how gold can still function as a trusted medium in global trade when confidence in fiat currencies falters.

Together, these arguments frame the gold and silver standard not simply as an economic proposal, but also as a protection against inflation and the erosion of trust in money during a time of growing global uncertainty.

The Case Against Metallic Standards

The view in favour of the return of the gold standard, however, is far from the mainstream opinion, instead the consensus views gold as a strategic asset and monetary hedge. Critics warn that a return to the gold standard would greatly reduce governments’ flexibility in applying monetary policy, as it constrains the ability to expand the money supply, one of the central tools for mitigating recessions and supporting growth.

It would also make global trade imbalances harder to manage, granting gold-producing countries a natural advantage over those without significant reserves.

Further doubts arise from the very foundations of US gold holdings: the reported 8,133 tons of reserves have not been comprehensively audited in decades, raising questions about both the actual quantity and the quality of the inventory. Some analysts also question ownership, suggesting that portions of the stockpile may be encumbered through swap arrangements with the IMF, BIS, or other financial institutions, despite being officially designated as Treasury assets.

Conclusion

Gold and silver’s comeback goes beyond market cycles; it reveals a growing distrust in fiat money. Central banks, investors, and governments are all turning to metals as strategic anchors in unstable times. Whether a temporary or structural shift, the return to “old money” highlights a deep uncertainty and fragile confidence about the durability of today’s financial system.