India’s real-money gaming (RMG) journey, once a $3.2-billion annual money-spinner, is over. This is courtesy a new law, The Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Act, brought in by the government just a few days ago. Apps such as Dream11, MPL, Zupee, WinZO, MyCircle11 and PokerBaazi have halted online games played with money, though at least one firm (A23) has reportedly moved the courts to challenge the ban. Paid contests are a space where, according to government estimates, around 45 crore players/accounts together lost over ₹20,000 crore each year. This much you may already know.

But what’s unknown to most of you, is, how it worked in the first place. Why did such a vast majority play online money games? Why did they regularly choose to lose their hard-earned money? And how did seemingly simple contests built on cricket, rummy or poker generate patterns of play that, in reported cases, led to debt, distress and even suicides?

Knowing how RMG became a monstrosity that scarred lives is very important. Because make no mistake, the playbook that powered RMG won’t vanish with the ban.

The rise of RMG

India’s appetite for gambling is centuries old, if not more. Dice games appear in the Mahabharata, card play spread in colonial clubs, and betting during Diwali became tradition. Often, these involved cash but in an informal and fun way.

The digital form of real-money games used that old instinct, but leveraged it at scale. Cheap smartphones, affordable 4G/5G data and the meteoric rise of UPI brought hundreds of millions of users online.

The legal environment, in a way, helped. Courts repeatedly held that games like rummy and fantasy cricket were “games of skill” rather than gambling. This interpretation allowed platforms to operate in a grey zone, even as some State governments (like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka) tried to control them.

The real breakthrough, however, was monetisation. Globally, most games earn money through ads, or “in-app purchases” (IAPs) such as buying digital skins, tokens or lives. But India’s ad rates (eCPM, the revenue an app makes per 1,000 ad impressions) are among the lowest in the world. Also, Indian players rarely paid for virtual goods. The domestic innovation was pay-to-play microtransactions — turning each entry fee itself into the purchase. For ₹10, ₹50 or ₹100, a user could join a contest and chase winnings. This solved the monetisation problem for RMG firms and scaled far faster than ads or IAPs ever could.

Into this gap flowed venture and private equity capital. Dream11 raised $840 million, MPL nearly $400 million, and WinZO $100 million from investors probably betting that India could produce its own gaming giants on the scale of Nintendo, Tencent or Electronic Arts. Investors didn’t see RMGs as gambling dressed up in apps. They saw a business model with clarity. Every contest generated revenue for the platform regardless of who won. Entry fees were tiny, but hundreds of millions of players meant huge aggregates. Frequency was daily, not seasonal. Customer acquisition was cheap, while global gaming software offered plug-and-play retention mechanics. All this meant a high margin, high repeat and scalable business. In an Internet economy starved of monetisation, RMG was the rare predictable cash engine.

For five years running now, India contributed over 15 per cent of global mobile game downloads — 2x share of the nearest two markets (Brazil and the US), according to the 2025 India Gaming Report. That vast empire was a result of the RMG becoming a mass market format, complete with advertisements, celebrity/influencer endorsements, sports team sponsorships etal.

Till its bust, RMG generated ₹86 out of every ₹100 earned annually by the Indian online gaming industry, as RMG-focussed platforms became household names. Some firms ended up generating more than 95 per cent revenue from RMG.

It was a model that delivered profits for platforms and investors, but created financial risks for players, making its eventual collapse probably inevitable.

Different formats, same outcome

The financial risks of RMG were not confined to one format. Each category tapped a different audience, but the outcome was the same: a majority of players lost money the longer they played.

Fantasy cricket and sports attracted students and young professionals during IPL and World Cup seasons. Entry fees were often low, but each user could make multiple entries (up to 20). Millions of teams were created in a single match. A tiny slice of winners took home large payouts, while a large share of players lost. A single high-profile match could see two crore teams, making small entry fees add up to massive aggregate losses if you played the entire season of 70+ IPL or 50+ Cricket World Cup matches.

Rummy was the first RMG offered in India. It was promoted as a skill game, but in quick online sessions luck often outweighed skill, and many players bled money quickly. The game was especially popular in tier-2 and tier-3 towns, where media reports pointed to growing cases of suicides and family disputes.

Teen Patti and poker catered to college youth and urban professionals. Poker relied partly on skill, but the built-in rakes and recurring top-ups meant players typically lost over time. Teen Patti was largely chance-based, with heavy losses common. Both formats usually provided chip systems that encouraged repeat spending.

Online versions of casual board games like ludo or carrom normalised betting by attaching small stakes to familiar formats. These type of games widened the net to homemakers, retirees and, reportedly, even minors, making the habit appear harmless while still draining wallets. Even when the stakes were only ₹5 or ₹10, repeat play meant players could end up losing hundreds in a day without realising it.

For many players, the lure went beyond cash. Platforms also flaunted prizes such as cars, bikes or iPhones etc. These added a visible, status-driven lure to winning, making it feel like a class upgrade rather than just a cash payout.

But no matter the format, the math stayed tilted.

Losing logic

The one constant across all RMG formats is that a heavy proportion of users lost. This was not an accident of chance, but a structural outcome of how the games are possibly designed and marketed.

At the core was the house rake — a fixed cut that platforms took from a contest pool. Even when players won, the platform always profited. On top of this, many apps disguised losses as wins. For example, if a user staked ₹100 and got back ₹80, the result was displayed as “You WON ₹80,” masking the fact that they were actually down by ₹20. Over time, such framing made repeated losses look less painful than they really were.

The genius of RMG was not in hiding difficulty, but in making every game look deceptively easy to win. The psychology of play added another layer. In fantasy sports or poker, users believed their “skill” could tilt outcomes, even though probability and large player pools made that unlikely. Near misses — finishing just outside a prize rank, encouraged persistence. Many fell into the sunk-cost trap, chasing earlier losses with bigger bets, convinced that one good contest would recover everything. This pattern of loss chasing quickly escalated small spends into unmanageable sums.

The economic impact was heaviest on lower- and middle-income players. A few ₹50 or ₹100 entries in a day looked affordable. But repeated across weeks and months, and that too on borrowed money, means all this snowballed into debts that families could not cover. Reports of players borrowing money, pledging assets, or even resorting to suicide revealed how quickly financial harm could spread.

Some other factors worsened the spiral. At a regulatory level, there were no hard caps on deposits, no enforceable limits on playtime, and no mandated cooling-off breaks after successive losses. And the marketing narrative of social proof made it worse. Ads highlighted stories of winners living a grand life, buying cars etc, while concealing the far larger base of losers. This survivorship bias made losses look like anomalies when, in fact, they were the norm.

Visuals that hook

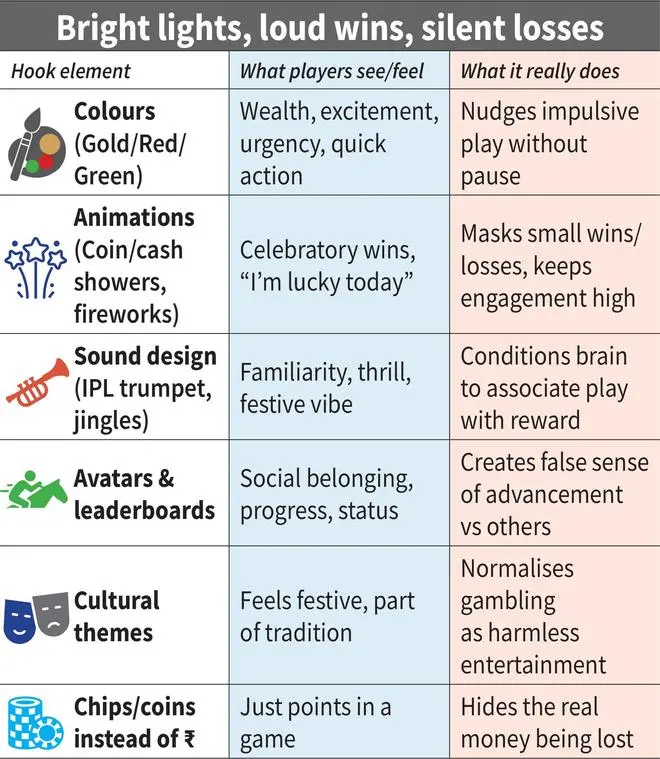

The experience of playing RMGs was never plain. Apps/platforms seem to have borrowed tricks from casinos to keep players engaged long after their wallets were lighter.

Colour schemes did much of the work. Gold and red were used to signal wealth, excitement and urgency. Green buttons invited players to “Play Now,” subtly nudging them to act without pause.

Animations amplified this effect. Even small wins triggered cash/coin showers, treasure chests or fireworks on the screen. Losses, by contrast, were shown in muted tones. This created an imbalance where victory felt loud but failure felt forgettable.

Sound design reinforced the above pattern. Loud jingles and celebratory tones marked every payout, however small. Quiet or absent audio accompanied losses, softening their psychological impact. Some apps even used familiar IPL signature trumpet sound or card-shuffling sounds to signal the start of a contest in a bid to call players.

Avatars and leader-boards added a social layer. Players could customise icons, see their rank and stats against others, and feel like part of a community. Lifetime stats of big winners were not much different than perennial losers, blurring the lines further. In reality, this often created a false sense of progress, masking the fact that most users were falling behind.

Cultural themes made the experience feel familiar. Rummy apps used Diwali motifs with diyas and lanterns. Fantasy cricket apps mimicked stadium-type visuals during IPL season. This ‘localisation’ made gambling behaviour look like part of everyday festivity.

Finally, chip-based currency in some games was a crucial abstraction. Instead of rupees, users played with points or coins. This made losses feel like a game, rather than real money leaving their accounts.

The visual layer was only the surface. Beneath it lay the code itself: algorithms and modules.

De-coding the code

Behind the flashy visuals lay something less visible. It is software designed to keep players engaged and spending.

AI-powered analytics tracked every click and hesitation. If a user paused before quitting, the system might trigger a personalised offer. Picture a small bonus, or a “last chance” pop-up to pull them back into play.

Matchmaking algorithms quietly could have shaped outcomes. New or weaker players, if often paired against stronger ones, made early losses more likely. Critics argue that design choices around matchmaking and card distribution often left new players at a disadvantage, prompting them to deposit again.

Reward modules built variable-ratio wins into the code. This meant small, irregular payouts which are just enough to keep users hooked, but rarely enough to offset overall losses. It mirrors the casino-style slot-machine logic that psychologists have long identified as highly addictive.

Near-miss animations created a sense of being close to winning, even though the underlying odds had not changed.

Payment systems added to the loop. Sure, deposits were made frictionless with one-tap UPI payments. Withdrawals, however, were a bit slower, and sometimes, subject to a subset of new rules. This nudged players to leave their balances in the app and play again.

Much of this technology may have been imported or adapted from casino platforms abroad but localised for Indian usage. Global investors with exclusive gaming portfolios also brought another layer: they may be connecting companies to proven software stacks, retention tools and behavioural analytics honed in other markets. This know-how meant Indian RMG firms weren’t just copying casino tricks, they were upgrading them. Together, these modules created an environment where psychology itself was coded into the experience.

Gambling brain

The science of why people keep playing and losing lies in how the brain processes risk and reward. At the centre is dopamine, a feel-good chemical produced in the brain and that regulates pleasure and motivation. Each time a player places a bet or enters a contest, the brain anticipates a possible reward. That anticipation itself releases dopamine, creating a high even before the outcome is known.

The most powerful driver is the variable reward schedule, the same mechanism behind slot machines. Wins arrive unpredictably. Sometimes they are big, sometimes small, and sometimes nothing. This unpredictability produces stronger dopamine spikes than guaranteed rewards, a principle documented in both Skinner’s classic experiments and modern neuroscience.

Near misses add to this pull. Finishing just outside a prize rank or seeing “almost winning” symbols activates the same brain circuits as actual wins, as shown in studies in the Journal of Neuroscience. This tricks players into feeling success is close, when in reality it is as far as the North Pole.

The illusion of control deepens the trap. In fantasy sports or poker, players believe skill or strategy can overcome chance. Psychologist Ellen Langer showed that even a small sense of choice, such as picking lottery numbers or making moves in poker, amplifies confidence and risk-taking, despite the outcome being completely random.

Over time, the brain adapts. Normal activities no longer release the same levels of dopamine. Players need higher stakes or longer sessions to feel the same rush. This mirrors substance addiction, where tolerance builds and dependence grows.

RMG did not only exploit wallets. They may have tapped into the brain’s reward system. The combination of anticipation, unpredictability and false control kept players returning, often against their own financial interests. That is how simple digital games escalated into debt, distress and, in some cases, tragedy.

The ban has shut the door on real-money games, but not on digital play itself.

E-sports, online social games and educational formats remain legal, and will likely grow. That is why it matters that we understand how RMG prospered.

The same tricks of colour, sound, psychology and code that kept players hooked could easily resurface in these new formats.

If those same tricks move into e-sports or social gaming, addiction will return under a different name.

Why it’s all a zero-sum game

“Not a question of enough, pal. It’s a zero-sum game. Somebody wins, somebody loses.” The memorable line, delivered by corporate raider Gordon Gekko (played by Michael Douglas) in the iconic movie Wall Street, was about traders. But it applies just as well to real-money games, lotteries or options trading.

Gambling, whether digital or traditional, feeds on two human impulses: greed and necessity. Some play to chase windfall gains, others to recover what they have already lost. Either way, the math is always the same: the pool doesn’t grow, it only gets redistributed.

Take a fantasy cricket contest during the IPL. Team entry fee was often small. Millions of teams were created in a single match. If two crore teams entered, the pool size on paper was about ₹100 crore. From this, the platform first took its cut. About half the teams lost their entire entry, while most of the rest still won back less than what they had put in. The over ₹20,000 crore lost each year in RMG wasn’t wealth created, just a Rubik’s cube of money endlessly twisted from one hand to another.

Lotteries work on the same principle. Millions of people buy tickets, each hoping to strike it rich. In reality, only a handful hit the jackpot while everyone else’s money funds those winnings. The total pot never grows. It is simply collected from the many and handed to a few.

Options trading too, when treated as pure speculation without hedging, follows the same zero-sum logic. For every trader who profits from a price move, there is another on the opposite side who loses the equivalent amount. Unlike investing in stocks where value can grow over time, these derivative bets simply shift money from one participant to another. So, the ₹1-lakh crore net loss each year for individual traders is an endless treadmill of capital.

The real danger lies not in the math but in the hope. Near misses, small consolation prizes, or the belief that “next time I’ll crack it” keep players hooked. The longer you stay in the system, the more likely you are to be on the losing side.

The RMG ban may have ended one cycle, but the zero-sum principle applies wherever risk is packaged as entertainment. Whether it’s fantasy cricket, cards or calls on Nifty, the math doesn’t bend: someone’s win is funded by someone else’s loss.

Published on August 30, 2025