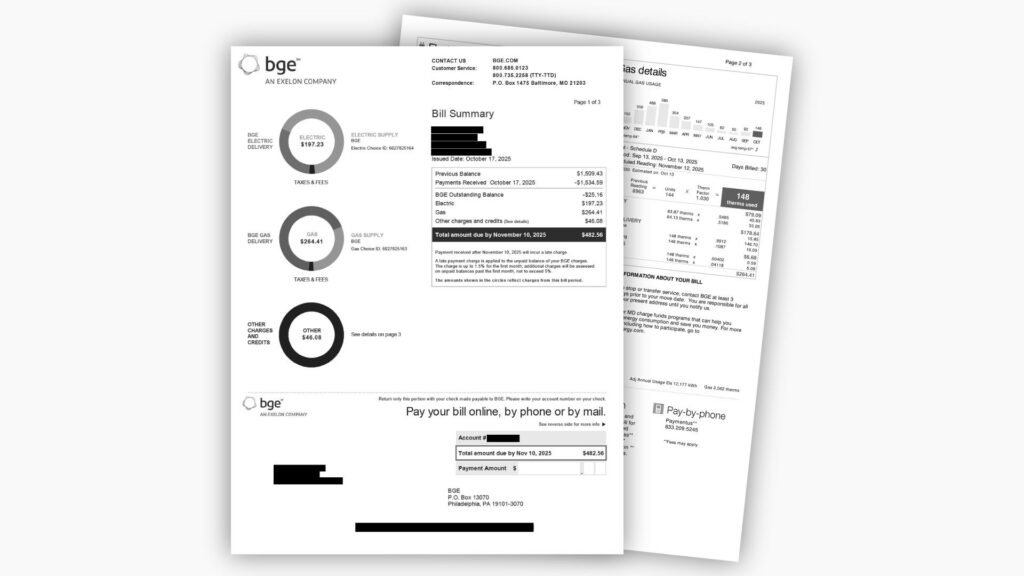

CNN dissects one customer’s October bill to show where and how costs can rise:

Desmond Stinnie was shocked to see a 4-digit number at the bottom of his utility bill earlier this year. He has lived in an old Victorian house in Baltimore for years, and the February bill from his utility Baltimore Gas and Electric was eye-popping.

“It does something to your soul when you see that,” he said.

Stinnie was not alone. Winter heating and electricity bills were extremely high for many Baltimore residents. The coldest months of the year often see the highest energy bills, but there is also a longer-term trend at play; since 2010, the rates BGE charges for distribution of gas have tripled and electric distribution rates have about doubled.

It’s not always clear to customers what that means. Residents who are trying to conserve energy and save money are getting frustrated when they see their monthly bill rising.

The terminology in electricity bills is challenging for the average consumer to understand, said David Hill, executive vice president of energy at the Bipartisan Policy Institute.

“It’s totally opaque,” Hill said. “There is no possible way for a normal retail consumer to ever figure any of this stuff out by looking at their bill.”

Customers often think of their utility bill as a reflection of what they use. But it’s also a reflection of what the utility builds. Across the country, ballooning bills are linked to the rising costs of updating aging energy infrastructure.

Baltimore Gas and Electric operates the oldest gas system in the country and is replacing hundreds of miles of the most ancient, leakiest iron and steel pipes. One pipe scheduled for replacement this year was first installed during Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency in the 1800s, said BGE spokesperson Nick Alexopulos.

“Our hundreds of miles of century-old gas main is far past the end of its useful life,” Alexopulos said. “We’ve got to upgrade this system.”

BGE crews have already replaced around 600 miles of elderly metal pipes with new, plastic ones and have around 800 miles left to complete, Alexopulos said.

On the electricity side of Stinnie’s bill, the highest costs come from “electric supply,” a shorthand for the actual energy Stinnie and other customers use.

There, rates are rising because of factors outside of the state. The entire Mid-Atlantic region is experiencing an electricity supply shortage as aging coal plants were decommissioned. That has collided with a demand explosion in the form of new, power-hungry data centers.

But as with gas, it’s the infrastructure — the poles and wires that carry electricity to our homes — that have been a huge driver of increased electricity costs nationwide, said Ryan Hledik, a principal at the Brattle Group and author of a recent study there on electricity prices.

Utilities across the country have recently been pouring money into upgrading their electricity infrastructure; in just five years, US utilities spent $5 billion on transmission (the massive high-voltage towers carrying electricity from one region to another) and another $16 billion on distribution (the smaller substations, poles and wires).

“We are seeing cost increases in both, but it’s just generally the case that those distribution costs represent a larger portion of your bill,” because serving residential customers at the local level requires more infrastructure than a cross-country transmission line, Hledik said.

Like Baltimore’s gas infrastructure, much of the nation’s electric distribution infrastructure is old. These systems have also taken beatings from flooding, high winds or wildfires. Meanwhile, equipment to replace them has become more expensive, driven by lingering post-Covid supply chain issues.

And experts say much of the nation’s electrical infrastructure needs upgrades to support the coming demands on the grid, everything from home electrification and electric vehicle charging to what’s been driving energy-bill headlines in recent months: data centers.

In Maryland, some of the new, modern equipment BGE is installing on their power lines will help bring power back on automatically after an outage, without a crew being sent to do maintenance. Other utilities are grounding power lines — literally burying the lines underground. It helps protect against power outages, but it comes at a high cost.

“Storms are stronger and more frequent, which means we need to harden our grid against storm-related threats like high winds and vegetation damage,” Alexopulos said. “This stuff is now just old and it’s past the time it needs to be upgraded.”