An international team of researchers has managed to unravel the best-kept secrets of the enigmatic bronze figurines of the Nuragic culture of Sardinia, known as bronzetti. Using cutting-edge techniques, the study has reconstructed the “biography” of these objects, from the extraction of the ore to their final form, revealing a complex network of interactions and metallurgical practices in the western Mediterranean at the beginning of the first millennium BC.

The figurines, which depict warriors, chiefs, animals, and ships, are one of the most iconic symbols of prehistoric Sardinia. For decades, archaeologists have debated the origin of the metal with which they were cast. Did the Nuragic people exploit their abundant local copper resources? Or did they depend on imports from distant places such as Cyprus or the Iberian Peninsula? The answer, according to this new study, is a combination of both.

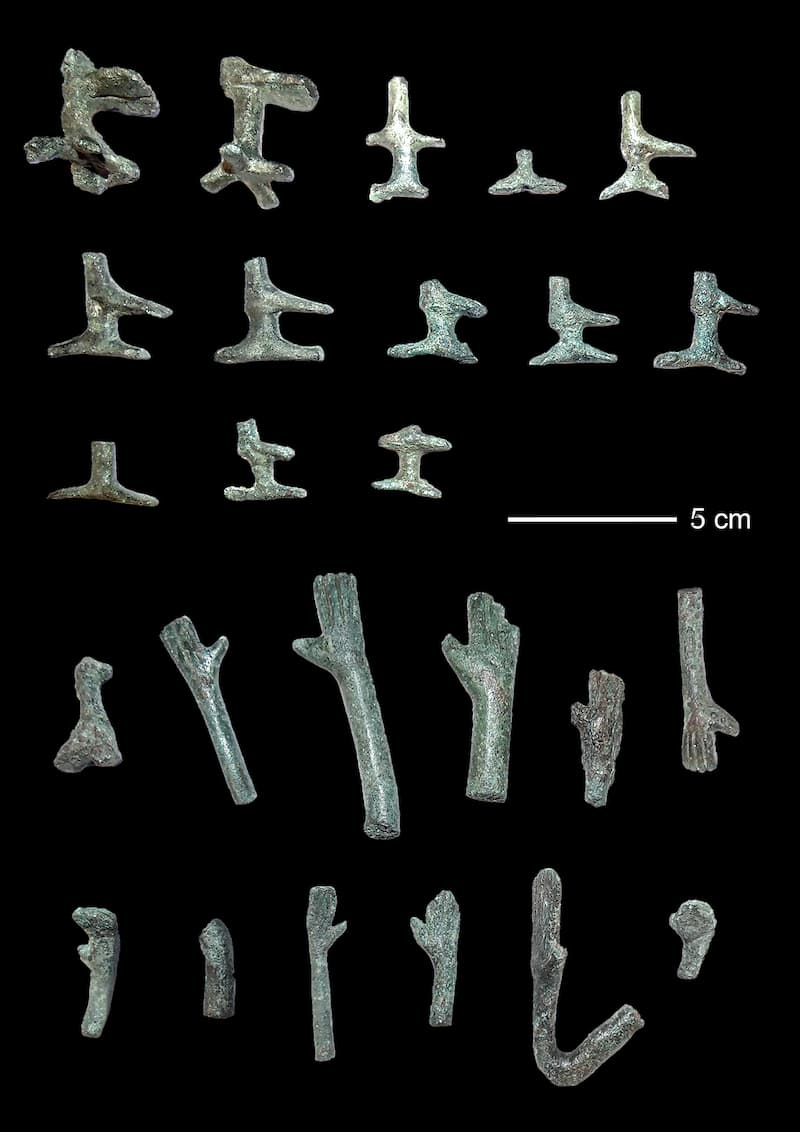

The study, published in the journal PLOS One, analyzed 48 fragments of bronzetti and three copper ingots from three key Nuragic sanctuaries: Santa Vittoria di Serri, Su Monte-Sorradile, and Abini-Teti, in addition to an unidentified site. Most of the samples are small parts of the statuettes, such as hands, feet, or helmet horns, ensuring that each fragment belonged to a different figure.

In addition to conventional chemical and lead isotope analyses, the scientists employed for the first time in this context copper and tin isotope analysis, and, in a pioneering way, osmium isotope analysis. This last technique proved crucial to solving a puzzle that had puzzled experts for years.

The Key Lies in the Mixture

The results are conclusive: the Nuragic artisans did not use a single type of copper, but rather mixed metals from different origins to manufacture their famous figurines.

The research employs an advanced archaeometallurgical approach, integrating conventional analyses of trace elements and lead isotopes with rarely used measurements of copper, tin, and osmium isotopes, the study explains. This methodological combination allowed for a more reliable identification of the original metal sources.

The data point to two main copper reservoirs:

- Sardinian copper: Most likely from the Sa Duchessa mine, in the Iglesiente-Sulcis district (southwestern Sardinia). This metal has a very distinctive isotopic signature.

- Iberian copper: Originating from the Iberian Peninsula, specifically from the Alcudia Valley region or the Linares district, in Sierra Morena.

The clearest evidence of this mixture was found in the figurines from the Santa Vittoria sanctuary. Their lead isotope ratios showed an “unnatural” correlation that can only be explained by the intentional mixing of two metals with different isotopic signatures. The concentrations of trace elements such as arsenic and antimony also supported this idea, showing that a metal rich in one element was mixed with another poor in that element.

One of the biggest problems in determining the origin of Sardinian metal was that its lead isotope signature overlaps with that of other regions, especially the Arabah Valley (Timna, Israel). This had led some researchers to suggest a possible Levantine origin for part of the metal.

This is where the innovative osmium isotope analysis came into play. The metal identified as Sardinian displayed extremely high and radiogenic osmium ratios. This highly distinctive pattern is not found in copper ores from the Levant but is consistent with molybdenite mineralization, a common mineral in Sardinia’s polymetallic deposits, including the Sa Duchessa mine.

We consider molybdenite to be the most likely source of the extremely radiogenic osmium isotopic signature and the high osmium concentrations in a portion of the bronze objects from Santa Vittoria, which in turn would prove a Sardinian origin for the copper, the authors conclude. This finding definitively rules out the idea that the local copper was actually imported copper to which Sardinian lead had been added.

Imported Tin and the Myth of Cypriot Copper

The study also addressed the origin of the tin, essential for making bronze. The analysis of its isotopes showed that the tin used was not local. The cassiterite deposits of Sardinia have a different, heavier isotopic signature. The researchers point out that the tin was most likely imported from the Iberian Peninsula, traveling along the same maritime routes as the Iberian copper.

On the other hand, the research settles another long-debated issue: the role of Cypriot copper. Although numerous Cypriot “oxhide” ingots have been found in Sardinia, the study demonstrates that this metal was not used in the production of the bronzetti, neither through its direct use nor through mixing or recycling. The isotopic and chemical signatures do not match. Cypriot copper stands out as a highly unlikely source for these local Nuragic products, the article states.

These findings paint a much more complex and dynamic picture of Nuragic Sardinia than previously thought. Far from being a passive receiver of metals, Sardinia was an active player in the trade networks of the western Mediterranean.

The exploitation of its own copper, especially from the Sa Duchessa mine, demonstrates an advanced knowledge of local resources. At the same time, the importation of Iberian copper shows stable maritime connections with the Iberian Peninsula. These results shed light on local metallurgical practices and distribution strategies in Nuragic Sardinia, but also on the broader role and position of Sardinia in the Mediterranean world during the transition from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, the researchers emphasize.

The study also supports the idea that the sanctuaries, where most of these figurines were deposited as votive offerings, were not only religious hubs but also economic and possibly metallurgical centers. They were places of wealth accumulation (ingots, metal fragments, finished objects) and displays of elite status.

SOURCES

Berger D, Matta V, Ialongo N, Nørgaard HW, Salis G, Brauns M, et al. (2025) Multiproxy analysis unwraps origin and fabrication biographies of Sardinian figurines: On the trail of metal-driven interaction and mixing practices in the early first millennium BCE. PLoS One 20(9): e0328268. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0328268

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.