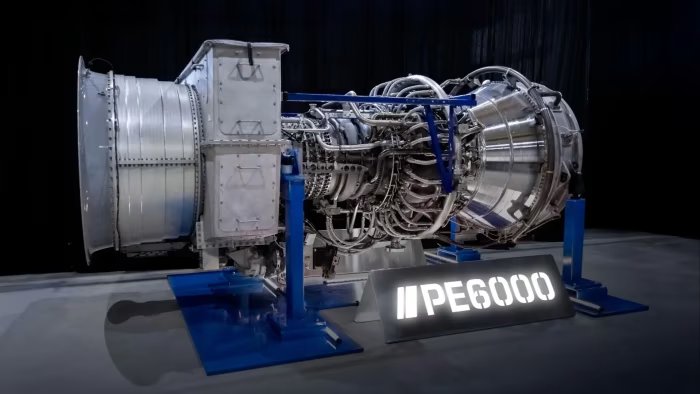

This year’s Data Center World Power show, held in San Antonio, Texas, produced an unexpected star turn: an industrial-scale gas turbine created from the retrofitted engine of a decommissioned passenger aircraft.

The high level of interest in this unconventional mini power plant — manufactured by power services group ProEnergy and which can produce enough dispatchable electricity to power up to 40,000 homes — illustrates the significant supply difficulties affecting the global power industry.

In the face of growing demand from megawatt-hungry artificial intelligence, coupled with an upward trend in consumer electricity use, global power demand is growing at almost 4 per cent per year.

Efforts by power producers to meet this rising demand have created a race to secure key components such as electric cables, switchgears, and turbines, leading to complaints of significant backlogs across a host of critical industries, says Fabricio Sousa, president of energy advisory firm, Worley Consulting.

Companies can wait up to five years to procure a large transformer or gas turbine, he notes, making supply shortages “one of the defining constraints” of AI’s acceleration. “We have a dynamic situation where demand is running at a sprint and supply at a marathon pace,” he says.

Factors other than just rising demand are also at play. The most obvious are tariff-induced disruptions to global trade in key components, particularly into the US. China’s rapid deployment of renewable energy infrastructure is also absorbing equipment otherwise destined for export.

But experts say the supply gap is not equal for all industries. The renewable energy sector, for instance, remains comparatively free of bottlenecks, thanks in large part to significant investment in manufacturing capacity and falling production costs over recent years.

“When it comes to batteries, electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, hydrogen electrolysers, all of this stuff, the market is actually heavily oversupplied right now,” says Antoine Vagneur-Jones, head of trade and supply chains at BloombergNEF.

Data centres are also comparatively shielded from the effects of supply constraints because of the market leverage that their greater spending power affords them. Even so, buyers that succeed in procuring critical components can expect to pay over the odds.

According to data collected by BloombergNEF, equipment shortages contributed to a 71 per cent increase in the US producer price index of power and distribution transformers between 2020-2024.

In response, many manufacturers are increasing production. Hitachi Energy recently committed to invest more than $1bn to expand its production of electrical grid infrastructure in the US. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, ABB, Siemens and GE Vernova are among others to have made similar scaling up pledges.

Building up more regional capacity represents another strategy adopted by manufacturers. Global energy technology specialist Schneider Electric, for example, operates a “multi-hub approach” in which it splits operations equally between France, Hong Kong and North America.

“This means we’re able to respond quickly and flexibly to shifting needs, supporting projects in regions where electrification and renewables are accelerating fastest,” says Frédéric Godemel, Schneider’s executive vice-president of energy management.

Even so, BloombergNEF’s Vagneur-Jones remains sceptical that such moves are enough to cover current backlogs, let alone meet future orders. Manufacturers could bet bigger, he says, but past experience is leading them to “play it very carefully” when it comes to scaling up.

“Back in 2017-18, they announced lots of new facilities in the expectation that gas demand was going to go up and thus demand for their equipment, but it didn’t and they got burned pretty badly,” he explains.

As a consequence, large-scale power users with the financial resources, such as data centres, are choosing to invest in their own on-site electricity generation. But, if getting hold of gas turbines is proving hard, what are the alternatives?

The list is long but complex to navigate. One possibility is smaller gas turbines, for instance. They benefit from a shorter wait time but, compared with their larger equivalents, their power output is lower and more expensive.

Another option being explored by data centres are combustion-style reciprocating engines. Again, these are comparatively easy to procure and deploy, but design limitations such as lower rotational speed and scaling challenges mean they are unsuitable as a primary power source.

Many alternatives are less than ideal. Some, like fuel cells, which create electricity from electrochemical processes rather than combustion, are too expensive. Others, such as geothermal or small-scale nuclear, remain experimental or take too long to install.

One possible exception is renewable power supported by battery storage, suggests Mike Hemsley, deputy director at the Energy Transitions Commission, a coalition of leaders in the clean energy sector. Even then, however, intermittency issues, low market penetration, and the high (albeit falling) cost of battery storage systems still present hurdles.

“The best alternative is probably a mix of solar plus wind plus batteries, together with a grid connection maybe and perhaps also some natural gas if you can get it,” he concludes.

Another way to ease supply-side pressures involves redesigning products. One cause of supply delays and high costs is the scarcity of rare earth metals and other raw materials that go into electrical equipment. Swapping in more readily accessible alternatives could present a way around this, as efforts to make electric cables from aluminium rather than copper illustrate.

In the attempts to resolve current supply problems, advocates of clean energy fear that moves by power producers to revert to fossil fuel-based solutions could stall the greening of the grid.

Claus Wattendrup, UK country manager of renewable power group Vattenfall, is adamant that such an eventuality can and should be avoided. What equipment manufacturers are lacking, he suggests, is a clear commitment by governments to press ahead with the energy sector’s electrification.

“For suppliers, consistent and growing demand is essential to justify investment in new manufacturing capacity,” he says. “But without the certainty that comes from stable policy frameworks and predictable deployment, the industry risks losing momentum.”