Motion at small scales is getting harder to engineer just as medicine, electronics, and robotics demand devices that can bend without breaking.

Researchers have now shown that rotation can come from a soft, flowing material rather than rigid parts, changing what engineers can build where stiffness becomes a liability.

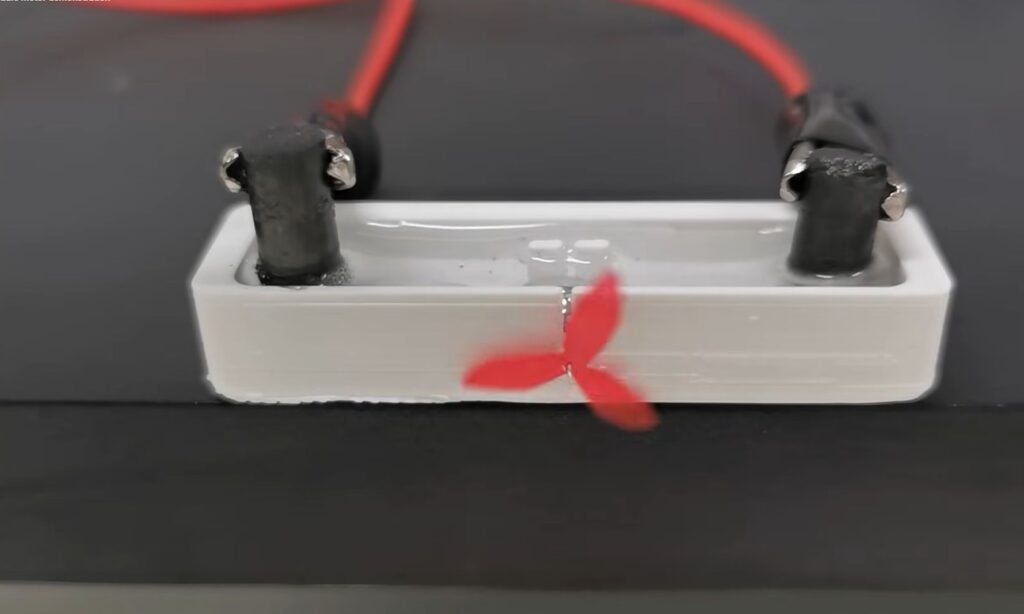

The work centers on a newly designed motor that generates spin using a tiny droplet of liquid metal instead of solid gears, coils, or shafts.

Engineers built a device that keeps working even when its main moving material stays fully liquid.

The project took shape at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, where engineers wanted rotation that survives bending.

Dr. Priyank V. Kumar, a senior lecturer at UNSW, focuses on devices that move when electric signals change a liquid surface.

That mindset treated rotation as a fluid problem, not a mechanical design built from stiff parts alone.

How the droplet spins

Rotation came from a droplet motor that drove a copper paddle by using a steady swirl inside liquid metal.

A salt solution surrounded the metal, and electrodes applied voltage that organized the internal flow into a single direction.

That moving metal carried the paddle around and reached 320 revolutions per minute during the team’s laboratory tests at UNSW.

The design stayed compact because the droplet itself supplied turning force without a separate shaft, gear train, or magnet.

Chemistry behind the spin

The researchers used a mixture of two metals, gallium and indium, that stays liquid at room temperature inside the device.

An alkaline solution dissolved the droplet’s oxide skin, and that cleanup kept the metal surface able to respond quickly.

Voltage redistributed charged ions along the droplet surface, which created Marangoni flow, liquid motion driven by surface tension differences.

That surface tension imbalance fed internal vortices that transferred force to the paddle instead of moving the whole droplet.

Pulses replace steady voltage

Timed electrical bursts drove the motor, and the team switched voltage on and off in set intervals to strengthen flow.

Current draw dropped by about half compared with steady driving, so the system wasted less power as heat.

The team saw rotation only within a window of applied voltage, which set practical bounds for control electronics.

Any future design must keep pulses stable, because noisy signals could disrupt the swirl and slow rotation over time.

Spin without stiffness

Soft robots bend and squeeze, yet they still need reliable rotation for tools, valves, or small wheels.

A recent review described liquid metal actuators, parts that turn energy into movement, as especially useful at small sizes.

Inside a soft body, the droplet motor could keep spinning even while surrounding material stretches or twists.

That advantage depends on careful packaging, because the motor still needs electrodes and liquid containment.

Motion inside tiny devices

Flexible electronics sometimes use fluid channels for cooling or sensing, and microfluidics – moving tiny liquid volumes through small channels – can manage flow.

A rotating paddle can stir or pump without bulky bearings, which matters when space is tight and surfaces are delicate.

Liquid metals already showed motion control through ion gradients in droplets, linking chemistry to movement without gears.

The new droplet motor extends that idea to rotation, but engineers still must keep the surrounding chemistry stable.

Materials and safety limits

The setup relied on sodium hydroxide, a caustic base that burns tissue and can cause severe injury.

Any device meant for hands-on use would need sealed chambers that prevent leaks and protect nearby materials.

Gallium alloys can wet and corrode some metals, so designers must choose compatible parts for long runs.

Those constraints mean early applications may stay in controlled lab tools before moving into consumer products.

Medical promise meets reality

Medical implants demand biocompatibility, safe performance inside the body over time, and the current chemistry would not belong in tissue.

Engineers could isolate the droplet in a sealed capsule, which would keep the corrosive solution away from the body.

Power delivery also matters, since wires limit where devices can go and batteries add bulk.

Even with smart packaging, regulators will demand long tests showing stable speed, controllable direction, and safe failure modes.

What engineers test next

Reliable control will require repeatable fabrication, since small changes in paddle shape or surface condition can alter performance.

Earlier liquid metal robots used voltage to drive motion in a robot, showing that liquids can already power practical movement.

A public report emphasized that flowing metal can turn a paddle while designers avoid traditional gears in compact devices.

“It proves that simple, flowing metals can drive rotation and opens the door to an entirely new class of motors,” said Kumar.

Rethinking how motors work

Taken together, the work showed that designers can get rotation from a liquid’s internal flow, not only from rigid assemblies.

Next comes building sealed, controllable versions that operate safely in real devices, including medical systems.

The study is published in NPJ Flexible Electronics.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–