For most people, buying their first home will be the biggest financial decision of their lives so far. The sums involved are intimidating, and the timing seemingly impossible to get right.

The sad reality is that the market will never be ideal, and there will always be political and economic uncertainty to give pause for thought. Here, we answer the key questions about whether the current environment is one in which to commit.

What do I need to buy a property?

In short, a lot of money. The average UK property costs just under £300,000, according to mortgage lender Halifax. This almost doubles to £540,000 in London. Most people therefore need a mortgage agreement with a bank to fund their purchase.

Is property becoming more affordable?

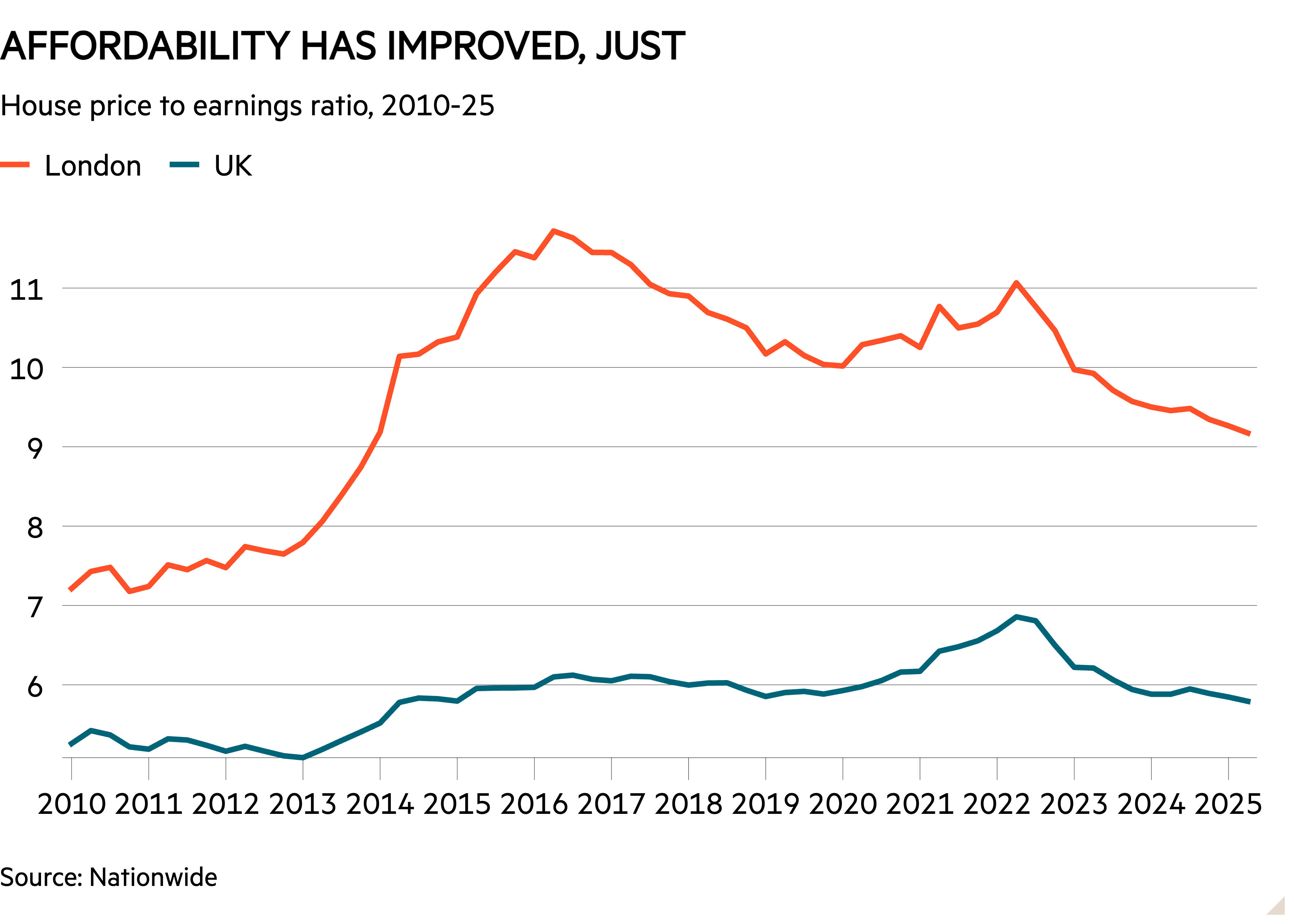

Yes, but from an intimidating starting point. Wages have grown at a faster rate than house prices for much of the past three years. The price of a typical UK home is now 5.7 times average income, according to Nationwide, down from a peak of 6.9 times in 2022 and broadly in line with pre-pandemic levels.

This trend should continue. “Housing affordability is likely to improve modestly if income growth continues to outpace house price growth as we expect.,” says Robert Gardner, chief economist at Nationwide.

How much can I borrow?

Most people can borrow up to 4.5 times their gross salary: someone earning the UK median wage of £40,000 should be able to obtain a mortgage worth £180,000. This equates to only 60 per cent of the average UK property price.

Doubling up unsurprisingly helps. A couple each earning £40,000 could together borrow £360,000, giving them greater financial firepower.

Positively, the regulator is temporarily – or perhaps even permanently – loosening criteria, so banks can lend to more people at a multiple above 4.5 times (this is currently restricted to 15 per cent of new mortgage lending).

Nationwide, for example, is expanding its ‘Helping Hand’ scheme. Under the scheme, it will lend to first-time buyers up to six times their income, a third more than they could obtain at the traditional limit. Lloyds is also getting in on the act, offering mortgages at up to five-and-a-half times income to its customers.

Read more on buying your first home

How big a deposit do I need?

The bigger, the better. The more a buyer can save, or borrow from the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’, the lower their mortgage cost will be. First-time buyers can secure a 95 per cent loan-to-value (LTV) mortgage, now that the government has made permanent its Mortgage Guarantee Scheme. This means putting down only a 5 per cent deposit.

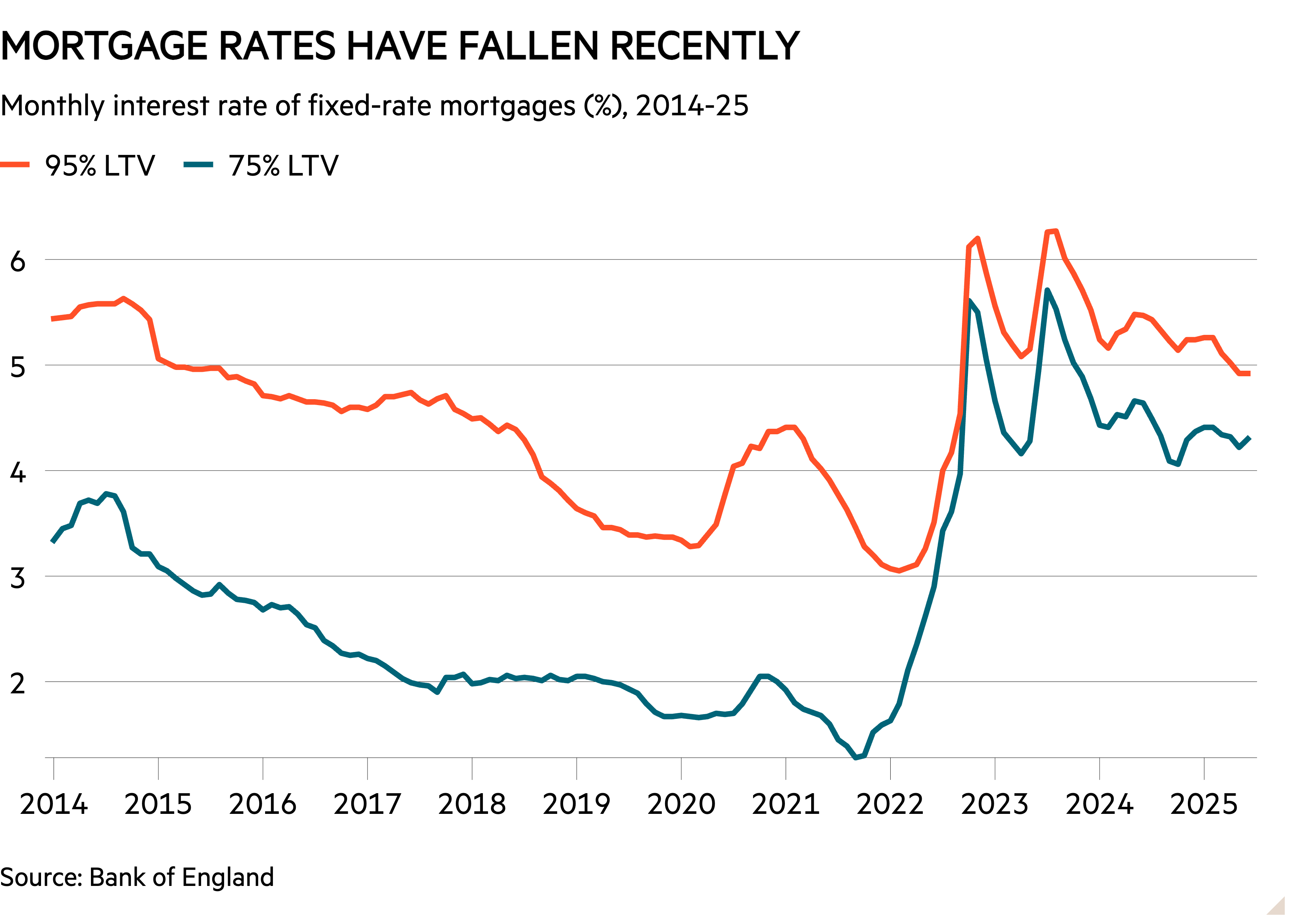

While these low-deposit deals boost accessibility, they do so at a higher marginal cost. Consider, for example, monthly repayments for a 30-year mortgage with a five-year initial fix on a £600,000 flat in London. These are £800 a month higher with a 5 per cent deposit than with a 25 per cent one, at £2,900 versus £2,100.

What are mortgage rates doing?

Mortgage rates have fallen from their recent peaks, in another boost for affordability. For that £600,000 flat in London, the average cost of a mortgage with a 25 per cent deposit has fallen from 5.7 per cent in the summer of 2023 to 4.2 per cent in September 2025. This is equivalent to a £400 reduction in monthly payments.

The cheapest mortgage rate for such a property is 3.52 per cent, according to moneysupermarket.com, which equates to a monthly repayment of £2,026.

NatWest chief financial officer Katie Murray recently spoke of “really intense competition” in the market during the bank’s recent Q3 analyst call. This is good for borrowers as it should put downwards pressure on prices.

Mortgage rates are still well above the levels of the zero-interest-rate era, however – something borrowers with lapsing five-year fixes are currently discovering to their cost.

It’s possible that rates could fall materially further. Following the Bank of England’s decision to lower its base rate to 3.75 per cent at its December meeting, markets now expect it to cut interest rates twice more during 2026, to 3.25 per cent.

The swap rates that lenders use to price mortgages have drifted down since October, but remain above this at around 3.5-3.7 per cent. If inflation falls towards the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target and the government can increase investor confidence in its fiscal credibility, then swap rates – and mortgage prices – can fall further.

And house prices?

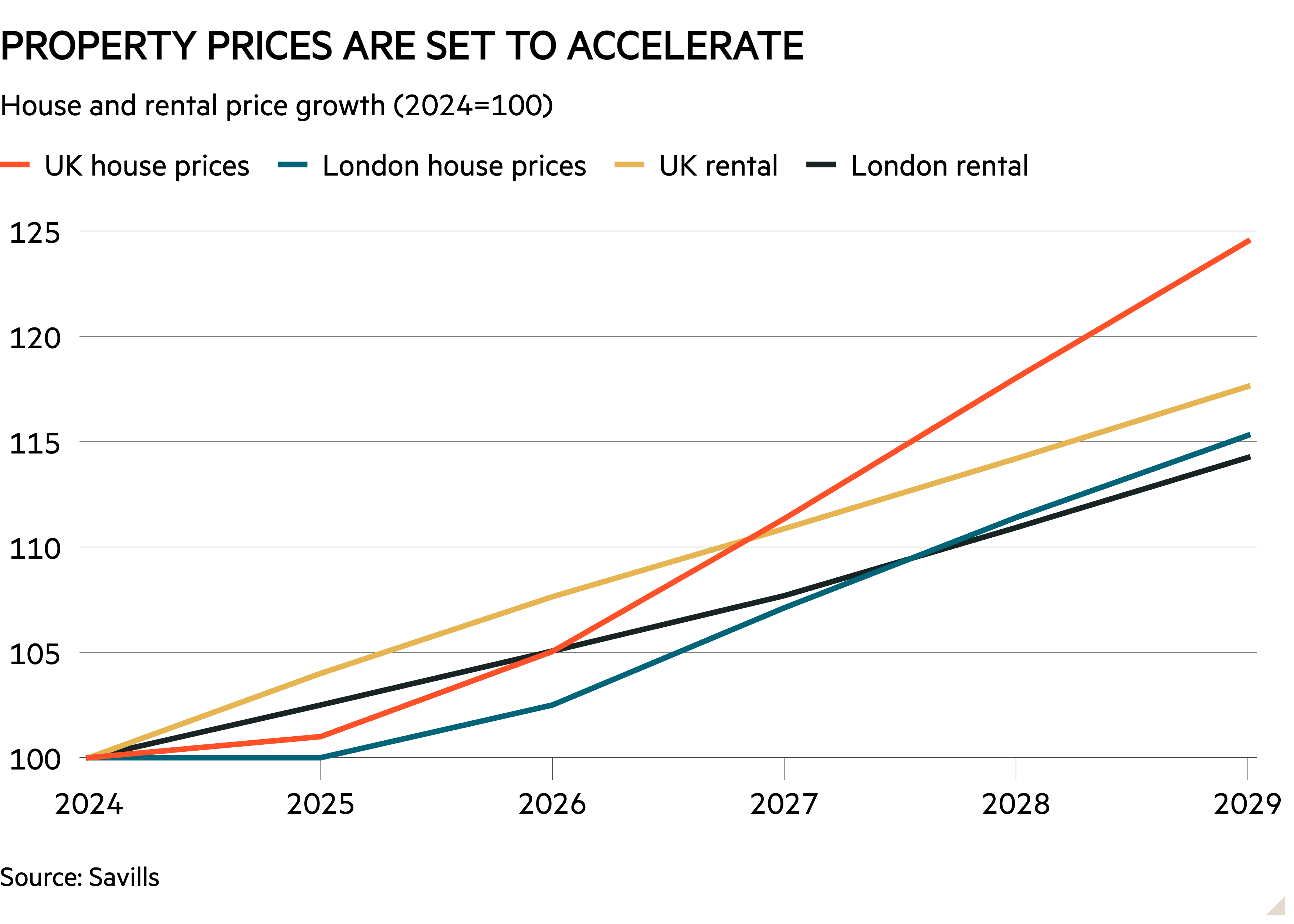

House prices have recovered to near-record levels, following a minor price shock during 2023. Although current growth is anaemic at less than 1 per cent a year, estate agent Savills forecasts this to pick up to 2 per cent in 2026, and at least 4 per cent from 2027 onwards. Wage growth would have to persist at close to current levels for the rest of the decade for affordability to improve much further, something that economists consider unlikely. Affordability may not be in the sweetest of spots, but nor is it in the most bitter.

Savills expects house price growth to vary widely by region, with growth stronger in Scotland, Wales and the north, but weaker in London and the south-east.

A price shock that materially reduces property prices might sound appealing to those not yet on the property ladder. But the accompanying economic environment would likely be grim (rising unemployment, a tightening of lending standards, slowing growth), such that any net benefit to affordability would be limited.

Are there lots of properties out there?

It is common knowledge that there is an undersupply of housing in the UK, especially in London and the south-east. And despite the government’s lofty rhetoric and proposed supply-side reforms, this is unlikely to change soon, as the number of new-build homes will take years to increase towards target levels.

After showing signs of improvement, availability has recently moderated. Rightmove recently commented that the number of new sellers coming to market in the second half of 2025 decreased 4 per cent versus the prior year.

The Rics November survey also pointed to a slowdown in new listings. There isn’t an abundance of choice.

An exodus of buy-to-let landlords from the market could improve supply. Many landlords are considering exiting their portfolios due to increases in taxes, borrowing costs and regulations, according to the National Residential Landlords Association, an industry body.

An increase in housebuilding activity would also improve things. Savills is forecasting only 160,000 new home completions for 2026, just over half the rate required by the government to achieve its housebuilding target of 1.5mn new home completions this parliament. If the government can encourage more housebuilding, whether through planning reforms or through easing affordability constraints, this will benefit first-time buyers.

Is it much harder to buy in London?

Yes. London is an outlier when it comes to affordability, for all the wrong reasons. House prices are 9.1 times average earnings, according to data from Nationwide. While this is the lowest level for more than a decade, it is still 50 per cent higher than for the wider UK, and prohibitively expensive.

The mismatch between supply and demand in the capital is only growing. There were just 3,500 private housing starts in London during the first nine months of 2025, according to research from Molior. The same research forecasts a depressing 11,000 private completions during 2027 and 2028.

For those able to get on the London housing ladder, mortgage payments account for more than half of take-home pay, versus a third nationally. While rental costs have at times dipped below mortgage payments in recent years, the difference is currently thought to be negligible.

Can renting be cheaper than buying?

While there have been times in recent years when elevated mortgage costs have made renting more affordable than buying, data from Rightmove suggests these periods are now behind us. The average first-time buyer with a 90 per cent LTV mortgage currently spends £200 less per month than the average renter, making buying a more attractive option for those who can afford to do so.

This, admittedly, varies by region. An April study by Hamptons suggested that renting was cheaper than the same mortgage in seven out of 13 UK regions, including London and the south-east. In no instance was the saving greater than 10 per cent, though.

There are non-financial considerations, too. Renters have more flexibility and a lower administrative burden. The recently passed Renters’ Rights Bill provides renters with more security, most notably by scrapping Section 21 ‘no-fault’ evictions and making it easier to challenge unreasonable rent increases.

Are there any other options?

One possible solution to getting a toehold on the housing ladder is shared ownership. Here, the buyer purchases a stake in a property – usually between 25 and 75 per cent – from a council or housing association, which continues to own the rest. The buyer then pays rent on the unowned portion of the property, and can increase their shareholding, known as ‘staircasing’, usually in increments of 10 per cent.

The buyer gets on to the property ladder with a smaller mortgage and deposit, and can increase their shareholding at their convenience. So far, so good. But there are trade-offs. As the properties are usually purchased from councils and housing associations, choice is limited. Shared ownership homes are also deemed riskier by lenders, and so tend to incur higher mortgage rates.

In addition to mortgage repayments, the buyer will also be paying rent on the unowned portion, along with leasehold charges and all maintenance costs. Shared ownership properties account for just 1 per cent of the UK’s total housing stock, which makes for a less liquid market, and potential difficulties when it comes to selling if the home remains part-owned.

What about impacts from the Budget?

November’s Budget did little to shift the dial for first time buyers. The government shied away from providing any fiscal support, such as through a stamp duty holiday or an equity loan scheme akin to the Tories’ Help to Buy, which ran from 2013-2023.

Under that scheme, the government would lend first-time buyers up to 20 per cent of a new-build property’s value (up to 40 per cent in London) for properties valued at £500,000 and under. The loan was interest free for the first five years and enabled buyers to purchase a property with a significantly smaller deposit or mortgage.

The government may yet introduce such a scheme in 2026 as its housebuilding target becomes increasingly challenging. “It’s not going to happen in the first half [of 2026] but we could see something put in place for the 2027 spring selling season,” says Investec analyst Aynsley Lammin.

What to do?

There are unlikely to be material changes to house prices, housebuilding, or mortgage costs and availability in the next couple of years. If you think your own financial circumstances could improve significantly in that time, or you are awaiting the silver bullet of Help to Buy, then it could be worth the wait. Otherwise, assuming you can afford to do so, now might be the time to put your best foot forward.