A rare copper nanocluster has been synthesised that behaves as a ‘superatom’. The Chinese team hopes it will unlock copper’s long-promised potential for sustainable carbon-to-fuel chemistry, turning carbon dioxide into valuable chemicals.

‘Superatom’ describes clusters of atoms that exhibit the properties of single elements or, in some cases, entirely new qualities. ‘These clusters can be made of potentially hundreds of atoms, but behave electronically, like a single large atom,’ explains Quan-Ming Wang at Tsinghua University.

Creating a copper superatom has long been desirable because copper is cheap, abundant and a catalytic workhorse. In the field of carbon dioxide valorisation – where carbon dioxide is converted into fuels and chemical feedstocks, like ethylene – copper-based materials interest chemists. Systems containing Cu(I)/Cu(0) interfaces are especially effective at encouraging the formation of carbon–carbon bonds.

‘Copper plays a pivotal role in C–C coupling … and shows great potential in converting CO₂ into multi-carbon products,’ explains Ahsan Ul Haq Qurashi at Khalifa University who was not involved with the study. ‘Remarkably, copper nanoclusters consisting of just a few atoms exhibit significantly higher efficiency compared to conventional bulk copper catalysts or copper nanostructures.’

Despite more than a decade of work, making stable copper nanoclusters that contain Cu(0) has proved extremely difficult, sidelining these materials. ‘The problem is Cu(0) is easily oxidised when exposed to air, and this problem is much worse on the nanoscale,’ says Wang.

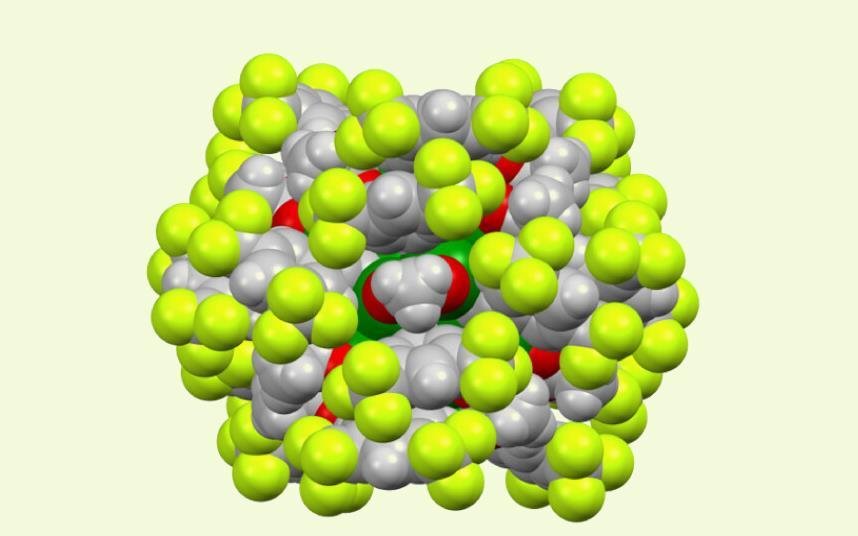

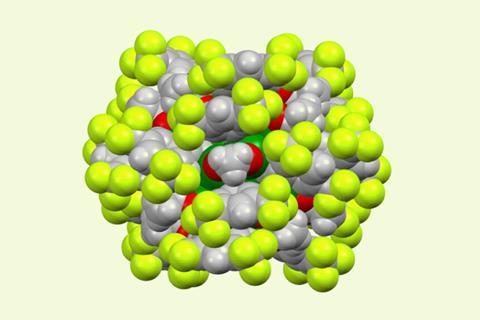

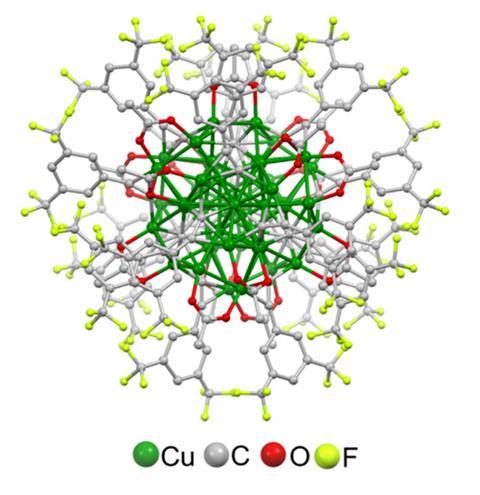

Wang and his colleagues designed a protective shell of organic ligands that bind tightly to the cluster, locking the atoms into a stable arrangement. The result is a new cluster, [Cu45H6(C≡CR)18(OAc)15] (or Cu45 for short).

‘It is resistant to heat, oxidation and reduction, as well as acidic and basic conditions,’ says Wang, ‘and survives longer than any other Cu(0)-based cluster known to date.’ Cu45’s ‘ultrastability’ is thanks to its electronic structure, which features a large energy gap that makes it far less prone to oxidation.

The team also tested Cu₄₅ as an electrocatalyst, finding that it converts carbon dioxide into multi-carbon products such as ethylene, ethanol and acetic acid with a high Faradaic efficiency. ‘This means 81.8% of CO2 was converted to multi-carbon (C2+) products, and 58% of the product was ethylene,’ says Wang. ‘The residual CO2 was converted into products such as carbon monoxide and methane.’

‘Prior to Cu45, copper clusters struggled to achieve high [product class] selectivity for multi-carbon products,’ says Wang. Cu45 outperformed standard commercial copper nanoparticles by 17% under the same conditions, and its performance rivals the best copper-based catalysts reported to date.

Ul Haq Qurashi is optimistic but foresees challenges. ‘This level of control on the atomic scale emphasises the practical relevance of these findings in advancing next generation electrocatalytic systems,’ he says. ‘One of the major challenges lies in enhancing CO2 solubility and achieving high selectivity toward desired C2 products. Addressing these issues is critical for translating such electrocatalytic systems into viable industrial applications.’

‘Advancements in these areas could pave the way for scalable and efficient CO2 conversion technologies, which can be potentially integrated with photovoltaics, making a significant impact on sustainable chemical manufacturing.’